Help prevent dementia-related wandering

By Mark MacLean

Stuart arose early, ready for a new day and excited about the prospect of a day doing the job he loved. He put on his favourite tie and headed out the door, briefcase in hand, to go to work as an insurance adjustor.

In reality, however, Stuart is 85 years old and has been retired for 20 years. He also has Alzheimer’s disease, a brain disease that can take those who have the condition back to a different time and place.

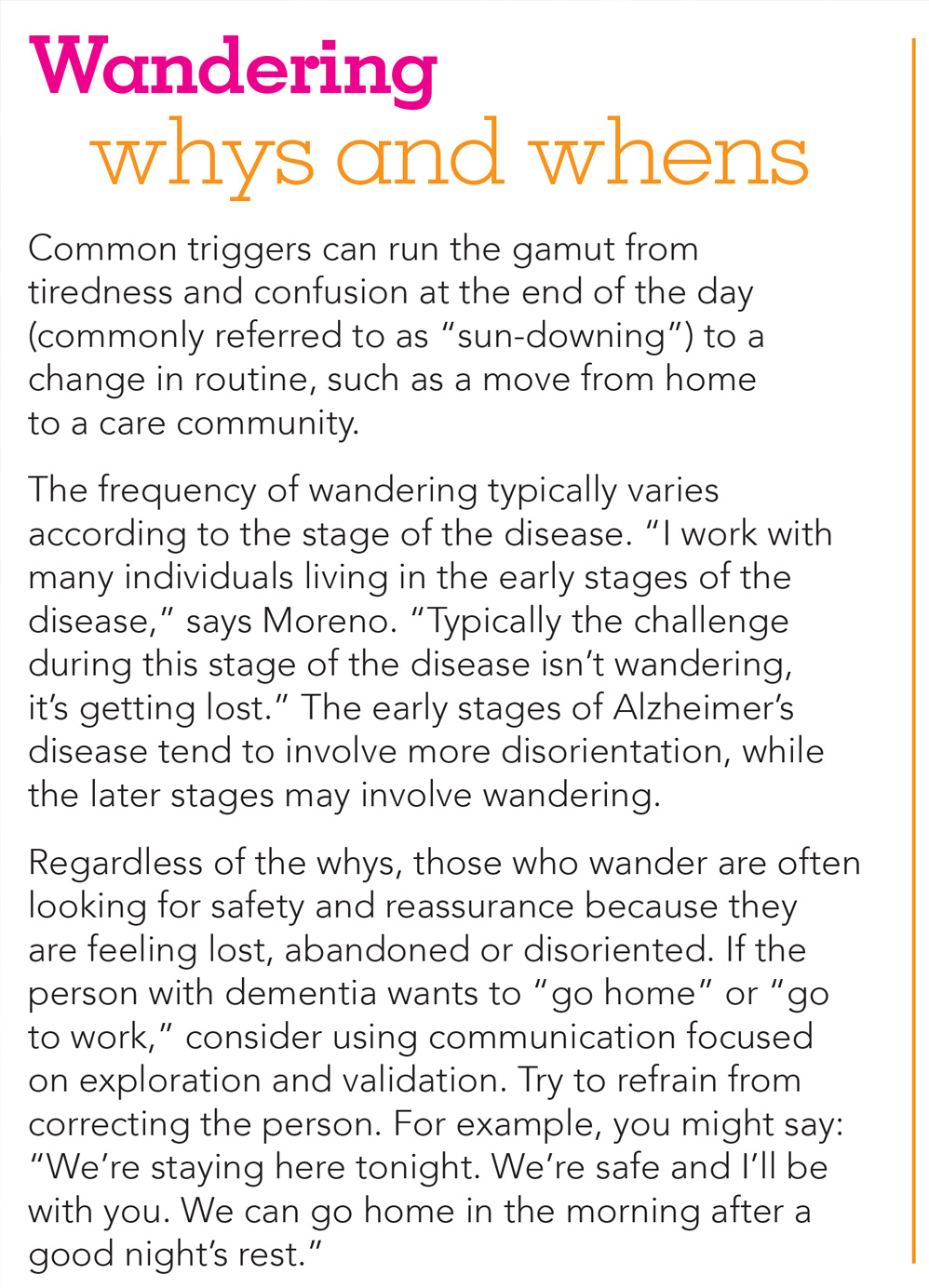

Wandering is one of the potential symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. According to a leading authority on the issue, those who wander often are trying to get to a familiar destination with a specific purpose in mind—such as a former job.

“A person may want to go back to a former job he or she had, even though it may no longer exist,” says Monica Moreno, director of early-stage initiatives for the Alzheimer’s Association. “Or someone may have a personal need that must be met. For example, that individual may be looking for the bathroom, but be unable to find it. So he or she goes searching and gets lost. There’s always a purpose and intent. It’s just a matter of identifying the triggers.”

With this in mind, family caregivers should watch for the signs that a senior may wander and take precautionary measures to help curb the risk. Doing so will go a long way to helping everyone stay safe and increasing peace of mind.

With this in mind, family caregivers should watch for the signs that a senior may wander and take precautionary measures to help curb the risk. Doing so will go a long way to helping everyone stay safe and increasing peace of mind.

Who’s at risk of wandering?

A wandering event causes immediate panic and can be one of the worst scenarios for the family of a person with dementia. Unfortunately, however, it’s a situation that occurs all too often. According to experts, six out of 10 people living with Alzheimer’s or dementia will wander at least once.

The reality is that any senior living with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia is at risk of wandering. Furthermore, the behaviour can affect individuals at all stages of the disease, as long as they’re mobile. Wandering can happen at any time and is not just limited to those on foot—individuals using wheelchairs or other mobility aids are also capable of heading out on their own.

A recent survey conducted by Home Instead Senior Care revealed that nearly 50 per cent of families have experienced a loved one with Alzheimer’s wandering or getting lost. Of those, nearly one in five called the police for assistance. Understanding why a senior may wander can go a long way in helping to prevent wandering episodes and locating missing loved ones without the need for police assistance.

Why do seniors with Alzheimer’s wander?

A common misconception about Alzheimer’s and wandering is that the individual who wanders often does so without purpose. One of the most frequent reasons a senior with Alzheimer’s might wander is due to the desire to go back to a previous home or to a former workplace. Individuals often don’t realize they are already home, or that they have been retired for many years. This might seem confusing to caregivers, but it’s vital to understand so families can prevent future wandering episodes.

Meet Dan

Dan’s wife of 50 years lives at home. The only problem is, she doesn’t know it. “A daily request is for me to take her ‘home,’ says Dan, “despite the fact she is home and is surrounded by her familiar home décor. She can’t say where home really is and my attempts for her to describe what home means have had no effect. It appears as if ‘home” is where she was a mother to our five children.”

That desire to go home is one of the common triggers for wandering in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. They often don’t realize they are home, so they are on a quest to try to get there.

The following points, from the Alzheimer’s Association, describe five common triggers that can prompt an individual with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia to wander, and explain what family caregivers can do to help.

1) Delusions or hallucinations. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease can misinterpret sights and sounds. Caregiver Evelynn says her mother wakes up in the middle of the night, insisting that someone is in the house and intent on doing her wrong. “I had to put an extra lock on the front door because she wakes up at night or from a nap in her chair and believes someone is at the door or on the porch, and she needs to let them in,” Evelynn says. As Evelynn has found, extra safety features are sometimes needed in a home to ensure a loved one stays safe.

2) Overstimulation. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease can  become easily upset when in a noisy and crowded environment. If that happens, they may try to escape from the chaos and wander. Avoid large, noisy places. Look for restaurants with quiet areas. Discourage big parties and family gatherings, or find a quiet room for your loved one to sit, then invite guests in to visit one at a time.

become easily upset when in a noisy and crowded environment. If that happens, they may try to escape from the chaos and wander. Avoid large, noisy places. Look for restaurants with quiet areas. Discourage big parties and family gatherings, or find a quiet room for your loved one to sit, then invite guests in to visit one at a time.

3) Fatigue, particularly during late afternoons and evenings. The later in the day, the more tired an individual with Alzheimer’s disease can become. This can lead to restless pacing back and forth. Furthermore, the shorter daylight hours during the fall and winter can often lead people with Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia to become confused about the time and become fatigued more quickly. Activities and exercises during the afternoon and evening can calm an individual and help to minimize the triggers for wandering.

4) Disorientation to place and time. Like Dan’s wife in the real-life example above, individuals with Alzheimer’s disease may not recognize they are already home. Avoid busy places that can cause confusion. Refrain from correcting the individual, and reassure the person he or she is safe. If the individual is feeling anxious, agitated or restless, take him or her for a walk.

5) Change in routine and unmet needs. Lydia had just moved to a long-term care community. Confused about leaving her familiar home, Lydia was found wandering in her new environment in an effort to make her way back to the place with which she was most familiar. Reassure the individual with Alzheimer’s disease that he or she is not lost or abandoned. And put safety features in place to keep that person safe. Establish a regular routine. Those who have Alzheimer’s disease do better in a structured environment. Because unmet needs also can trigger wandering, make it a practice to suggest a loved one go to the bathroom after a meal.

Keeping your loved one safe

While you can’t stop someone with Alzheimer’s from experiencing the urge to wander, there are precautions you can take to help keep them safe.

Ensure your loved one wears identification. The number-one thing you can do is ensure that an individual at risk always wears a form of identification, such as a bracelet from the MedicAlert Safely Home program. This is a fee-based, 24-hour nationwide emergency-response service for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease or with a related dementia who wander or have a medical emergency.

Reduce the likelihood of outside wandering. Many products exist on the market to help keep older adults with dementia safe at home. These include alarms that attach to the doors and windows, covers for doorknobs that help prevent an individual from leaving the home and higher-security locks or motion detectors throughout the house. Other strategies include placing locks out of eye-level view, and painting doors and door frames the same colour as walls to “camouflage” exits.

Make the home safe. It’s also important to realize that wandering can happen within the home. To keep seniors safe at home, make sure that walkways are well lit and clutter free. Closing off certain parts of a room or locking doors will help to create a path that is less likely to cause individuals with Alzheimer’s to become disoriented or confused. Extra lights at entries, doorways, stairways, and areas between rooms and bathrooms will also help to minimize the possibility of accidents due to wandering.

Meet Arlene

A caregiver named Arlene says her husband often awakes at night not knowing where he is or thinking it is time to get up. “So we put a motion detector in the bedroom,” she said. “That has worked well for me.”

Tips to be proactive about safety and wandering

Make a path in the home where it is safe for an individual to wander. Closing off certain parts of a room or locking doors can help achieve this goal. Such paths can also be created outdoors—in a garden, for instance.

One family caregiver remembers her husband getting outdoors in the middle of the night in the dead of winter. “A fence kept him from wandering from home, so he went into the garage. He was banging on the door at 5 am, which woke me up. If he had gotten out of the

yard, he would possibly have died from the cold.” Install barriers and fences in yards to help ensure that a loved one doesn’t wander from home or into unsafe territory.

Keep walkways well lit. Add extra lights to entries, doorways, stairways, and areas between rooms and bathrooms. Use night lights in hallways, bedrooms and bathrooms to help prevent

accidents and reduce disorientation.

Place medications in a locked drawer or cabinet. To help ensure that medications are taken safely, use a pill box organizer or keep a daily list and check off each medication as it is taken.

Remove tripping hazards. Keep floors and other surfaces clutter free. Remove objects such as rugs, magazine racks, coffee tables and floor lamps.

Be proactive

Learning as much as you can about Alzheimer’s- and dementia-related wandering will go a long way in not only keeping senior loved ones safe, but also reducing caregiver anxiety.

Try these tips from preventingwandering.ca

• Know your environment. Are there lakes, wooded areas or shopping malls that could attract an interested senior? What has the

individual been talking about? Was there a mention of wanting to visit someone or a specific place? Keep a list of the places where your loved one may wander.

• Be prepared if a loved one becomes lost. Register with the Missing Senior Network program. This free web service helps family caregivers to create a list of contacts they can alert should their loved one go missing. The service enables caregivers to notify their network of friends, family and businesses in the event a loved one become lost.

• Combat anxiety, agitation and restlessness with reassurance and diversions. The more anxious a loved one becomes, the more likely he or she could be headed out the door. During those times, provide activities that can divert and entertain. Also reassure the person that he or she is safe and that everything is OK.

• Educate others. Tell as many people as possible about the disease—from trusted neighbours and shop owners, to the staff of restaurants where your loved one likes to eat—so they are aware.

• Ensure constant supervision. Too much activity or noise can trigger a “flight” reaction. Avoid large, noisy gatherings and crowded places. As dementia progresses, your loved one may need constant supervision to remain at home. This is not something you should try to do alone for extended periods.

• Take care of yourself and get help. You’ve heard it before, but it’s true: You can’t be a good caregiver unless you first take care of yourself. Keep up-to-date on medical check-ups and get respite help.

Mark MacLean is the Managing Director of Home Instead Senior Care Toronto West.