Our parents may be living longer—much longer. So how can we cope with this extended journey?

By Pat Irwin

Kathie’s day begins at 6.30am. She cycles to her daughter’s house to look after her two grandchildren—both under the age of five years. That “shift” finishes at 4pm. Then, on most days, she heads over to see her 93-year-old mother, Marjorie, who is quite frail and now lives in a nursing home nearby. Kathie visits for a while, and makes sure Marjorie eats her dinner. Marjorie’s lost weight since she moved into the home and doesn’t like to eat with the other residents.

As she put her mom’s supper dishes back in the server, one of the nurses stops by to say hello. She updates her on Marjorie’s health, saying, “Your mum’s looking much better today. You’re so lucky to still have your mother around.”

Don’t misunderstand. Kathie adores her mom and is well aware of how lucky she and her brothers are to still have their mother in their lives. She enjoys the fact that her mom knows her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. But while she doesn’t complain, Kathie feels tired … and a bit overwhelmed by her never-ending family responsibilities. She wonders how many other people are dealing with similar issues.

The new “very old”

How common is a very old parent? More Canadians are reaching 90 or even 100 years of age, with centenarians being the second fastest-growing age group. Today, a senior reaching the age of 90 can expect to live for another five years. Chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, and even cancers such as leukemia can be managed with medication and lifestyle changes and are no longer the death sentences they might have been in previous generations.

Although the most common age at death for Canadians is 85 years, the ability of many adults to perform key health functions declines with age. This means that the average Canadian can expect to live roughly 10.5 years with some level of disability.

What can someone like Kathie, with 25 years of caregiving experience, teach us? Here’s what she has to say about the practical, financial and emotional elements of caregiving.

Recognize that money drives many decisions

Each of the things your loved one needs—be it nursing care, companionship at home, a suite in a retirement residence or a long-term care facility—has a cost. There’s often equipment too. And you might have a mom and dad to care for at the same time.

Some things can be estimated and planned for, but the wild card is care. Care services from an agency range from $20 to $30 an hour for a personal support worker; for 24-hour care, that’s about $700 a day. In contrast, a retirement community suite could cost $4,000 per month, with care costing another $1,200 per month—but a 400-square-foot suite is not “home.” The good news: Long-term care homes are subsidized by the provincial ministries of health, so the resident’s monthly cost might range from $1,800 to $2,400, depending on the type of room.

Some families choose to provide care in the family home for as long  as possible; the sale of the family home typically funds an extended care journey. Other families opt for a high-end, costly retirement suite for as long as it’s affordable, then move their loved one to publicly funded accommodation “when the money runs out.” Timing is often hard to factor, as there may be delays for equipment and waiting lists for retirement homes or long-term care facilities.

as possible; the sale of the family home typically funds an extended care journey. Other families opt for a high-end, costly retirement suite for as long as it’s affordable, then move their loved one to publicly funded accommodation “when the money runs out.” Timing is often hard to factor, as there may be delays for equipment and waiting lists for retirement homes or long-term care facilities.

In the process of becoming a caregiver, get professional help to strategize, budget and plan. For example, you might want to consolidate accounts; automate payments to reduce your paperwork, know when fixed-term investments are due and anticipate when they will be needed, and ensure powers of attorney (and valid alternates) are in place.

Know the options in your community for subsidized care, day programs, respite programs, retirement communities and reputable care agencies. Do your homework now so that you have the contacts, costs and wait times to hand when you need them

Realize there will be personal costs

I am aware that I’ve paid my own financial and personal price, and what it costs other women to care. I’ve given up full- and part-time jobs to help my daughter and mother. My colleagues were initially understanding, but in the end I ran out of sick and vacation days, I couldn’t work overtime and there was no way I was promotable because I couldn’t always be “on call.”

Learn to pace yourself

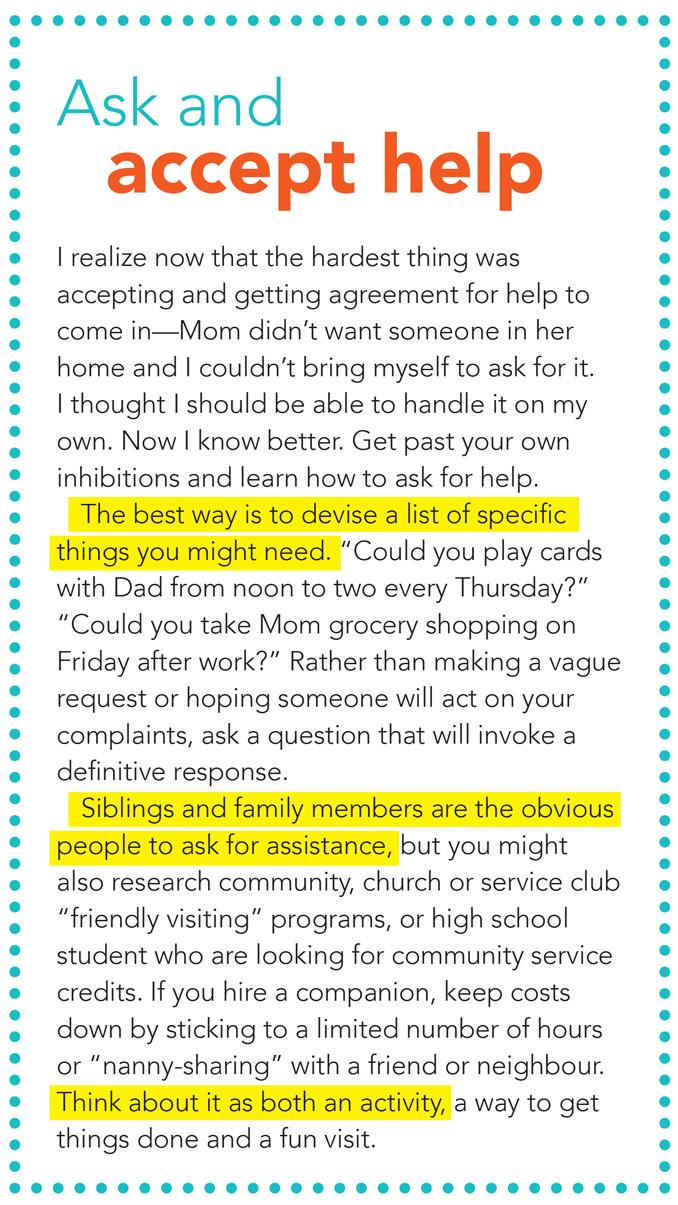

Wherever I am, I feel I should be somewhere else! I find it important to pace myself and find time for respite from the caregiving marathon. I’ve learned to ask for and build in “me time.”

Many caregivers regularly book their parents for respite stays at retirement communities or nursing homes. Some agencies offer move-in respite care. Family members can be recruited, possibly with some hired assistance. A respite period of two weeks is recommended — any shorter and the person doesn’t have time to settle in, or the caregiver to truly recover. Shorter scheduled respite arrangements can also be effective. Knowing you’re off-duty for the same day every week allows a caregiver to pursue their own personal life.

Think practically

Caregiving is demanding. It’s a known fact that family caregivers experience stress and disruption of their own well-being and social activities, and are at risk for increased mortality, coronary heart disease and stroke. Caregiving takes time from supports such as colleagues, spouses, children, friends and hobbies, and caregivers often feel “invisible.” They might also experience depression and be more prone to illness themselves.

Help yourself by understanding that there are things you just have to let go. Whether your parent is at home with care or in a care community, you cannot control every aspect, all the time. You have to choose your battles and learn when to insist and when to let things go.

Respect the caregiving policies and procedures of a retirement home or homecare agency. You know your parent, but they know professional caregiving.

Last but not least—be patient

Try to position yourself positively within your loved one’s care community. No one likes to be yelled at or treated badly. Professional caregivers and managers—as well as your family members and friends who have decided to step up and help—are your partners. You’re a team, with everyone having valuable input and a role to play in keeping your relative or loved one safe, happy and healthy.

Pat Irwin, BA, AICB, CPCA, is President of ElderCareCanada.