By Helene Berger

I did not recognize, when we received Ady’s diagnosis, how vastly my own life was about to change. Nor did I take stock of what abilities I might utilize to keep our lives as comfortable as possible. The more you are able to accept that your own life will never be the same, the better you will be able to deal with the challenges ahead.

Acceptance takes not only work but time. The daily demands are not going to go away. The sooner you accept this new, harsh reality, the more energy you’ll have, and the more focus you will be able to direct to the strategic planning necessary.

Learning from everybody

The rabbis say: “Who is wise? One who learns from every person.” * The following short vignettes illustrate how we can begin to function in a responsible way only when we come to terms with reality.

Life goes on

When I look back, wondering if I had the strength to cope with the difficulties that lay ahead, I thought of decades earlier when I got the call that my mother had died. The news was expected but still devastating. My beautiful, accomplished mother was fifty-two. I was twenty-two. When Dad’s call came in, I was giving breakfast to our first child, who was eight months old. This was not the time to fall apart. I pulled myself together, knowing that I had plenty of time to grieve and mourn later. I had just lost my mother. I needed to feed my son. Accept both realities. Life goes on. It was a powerful lesson.

The soothing finality of facts

Ady and I were on a plane headed home to Miami. A man and his wife were seated in the aisle directly across from us. Their daughter’s flight had been cancelled and the man was trying to get her a seat on this one. The man was in a rage: he saw nothing but empty seats, but the stewardess kept telling him that the flight was full. Slowly, the seats around us filled up. All were occupied. Once the man accepted that nothing more could be done, he became docile, reading a book the entire flight and behaving like a perfect gentleman.

It was an important learning experience for me, offered unconsciously by a total stranger: When we cannot change the facts, we experience useless anger until we accept them—and a sense of calm when we do.

A friend’s guidance that helped to sustain me

In the early years of Ady’s incipient Alzheimer’s, I had expressed my concerns about Ady to none but my closest friends. We were out to dinner with a lovely couple whom we knew well. Although we had known them for years, Ady turned and said, “So, Sam, what do you do?”

I blanched and tried to come to Ady’s rescue, but Sam’s wife, Lynn, took my hand and said, “Helene, everybody loves Ady for Ady. Don’t try to cover for him.”

My eyes filled with tears realizing how obvious Ady’s deterioration was. Trying to keep secret what had become clear to others only made it more difficult. When we deny the reality, we lose the wise counsel and compassion that friends can offer. The willingness to be open afforded me the opportunity to learn from other’s experience. Lynn’s guidance was my first step toward open, public acceptance of our new reality. Ady himself made it easier, as he began to openly admit, “My memory’s not so good anymore.” In two six-word sentences, Lynn’s honesty and compassion changed my life.

Coming to terms with the patient’s capabilities

The struggle to accept a “dread decree” like Alzheimer’s, dementia, or life with chronic pain can often last for years. Every degree of decline on the part of our spouse or loved one is a new punch in the gut. We still want and expect the old behaviour, and debilitating anger begins to seep in. I found that my own acceptance varied from issue to issue. Some problems were easier to accept, while others put me into a tailspin.

For example, though I was able to accept Ady’s loss of memory quite early, it took me much longer to accept that this brilliant, mathematically- inclined man could no longer manage his time or had difficulty with simple arithmetic. What was worse, when I expressed my annoyance, Ady would look at me like a wounded puppy. He was simply no longer capable of planning his own time. My expectations had to change.

The power of data

While I spoke earlier about some limitations of psychological testing, the testing that followed, a brain scan, was one that changed my life. The doctor pointed out on the scan, large areas of black empty spaces where brain tissue should have been, and said, “If I had seen this scan before speaking with Ady and seeing his excellent test results, I never would have believed that anyone with this much damage could do as well as he did. He wants to. He just can’t.”

With those words, I got it. The results of the brain scan I viewed evoked both my complete compassion and the ability to move on. The fight was over. Witnessing the brain scan results freed me to appreciate the man that Ady still was.

My role was to give this precious, sweet, loving man the love and support he needed and deserved. It was humbling to know that despite my managerial skills and commitment, despite the ideal atmosphere that I tried to create with determination, with energy, with incalculable time, I now understood that I was not that powerful.

The patient’s own acceptance

To make life easier for everyone, we try to encourage the patient’s own acceptance. That, I’m afraid, is the most difficult to achieve. But I believe that, even here, your own attitude can make a difference. If you treat your new role with frustration and annoyance at every diminution, that anger will spread to your patient like a virus. The more you can muster up support and kindness, remembering always that he or she did not choose this condition either, the more likely it is for your loved one to understand that you are there for the long haul and that he will not be abandoned.

Once Ady got over his initial depression and understood that I was there for him 100 per cent, he began to accept his changing condition with more grace than I thought was humanly possible. His positive attitude, in turn, affected me profoundly.

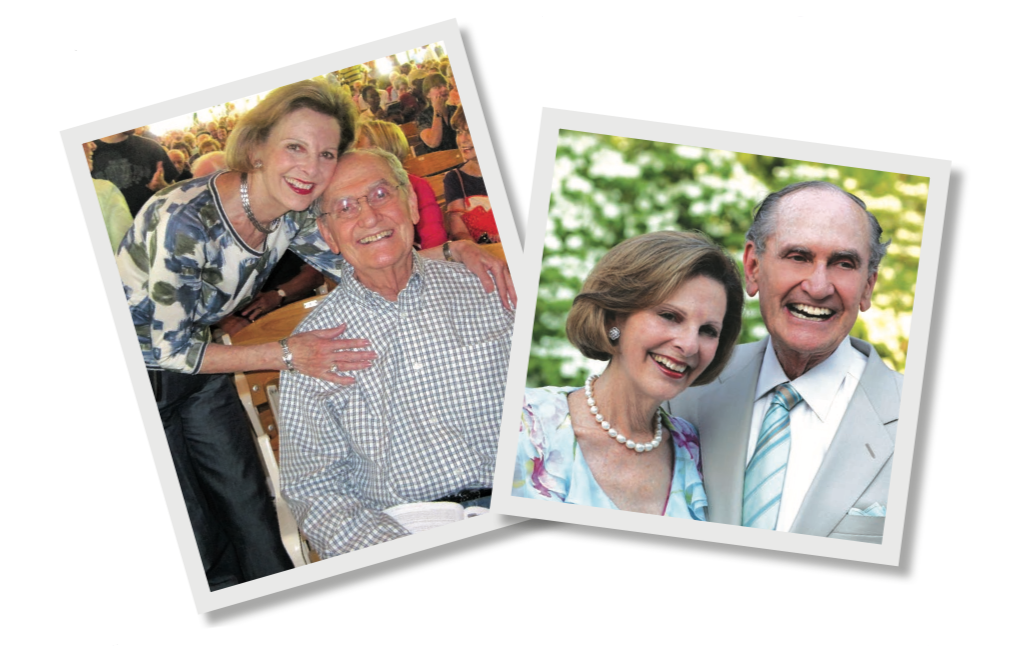

I can honestly say that after more than fifty years of marriage, my love for and appreciation of my husband not only did not diminish, but grew. The love he felt from me was completely authentic, and he thrived on it. Knowing that I had a lot to do with his radiant smile made me happy. Virtually every night, after his good-night kiss, he still expressed with varying words, “I love you so much, and I appreciate all that you are doing for me.” He expressed his own appreciation and love for me verbally and in writing—and I, in turn, thrived on that. After the first year I stopped thinking “poor me” and began thinking “lucky me” to be married to such a man.

I understand how fortunate I was with the outcome we had. I certainly understand that every Alzheimer’s patient will not react as Ady did. Yet I strongly believe that the more one can create a loving atmosphere, the more one can soften or avoid any expression of disappointment or impatience, the more likely the patient is to thrive.

Separation and guilt

In the beginning, I became aware that I needed to separate myself slightly, or the pain was too great. That subtle pulling away gave me the perspective to cope. However, when I realized that my initial instinctive behaviour was partially for my benefit, my emotions were compounded with guilt, even though that slight pulling back was only for a very brief period.

I record this harsh self-judgement because I think that at some point, all of us as caregivers add a feeling of guilt to our other burdens. No matter how hard we try, there are days when we’re sure we’re not doing enough. I think it’s important to recognize that those questions and feelings, though understandable, are not productive. Whatever we do to keep ourselves functioning, whole, and sane is necessary. We are often more generous about the failings of our loved one than we are about our own. We need to give ourselves permission to be human.

The family’s reaction

If your family is not responding in a way that offers compassion and support, it may take more than one conversation on your part to help them understand that this debilitating condition is not one that their loved one has chosen. You might encourage them to remember the good times they have had together, or the positive contributions the afflicted patient has had in shaping them.

You are all embarking on a new relationship. The old expectations are no longer valid. How your family approaches these changes will have a major impact on their relationships with both you and the one who is wrestling with Alzheimer’s. It will be a new relationship, to be sure, but, with caring and effort, it can be a deeply

satisfying one.

Dementia Facts

5% The percentage of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s budget invested in dementia research

45% The greater your risk of developing dementia if you smoke

65% Of those diagnosed with dementia over the age of 65 are women

16,000 The number of Canadians under the age of 65 living with dementia

25,000 The number of new cases of dementia diagnosed every year

56,000 The number of Canadians with dementia being cared for in hospitals even though this is not an ideal location for care

564,000 Canadians are currently living with dementia.

937,000 The number of Canadians who will be living with the disease in 15 years.

1.1 million The number of Canadians affected directly or indirectly by the disease

$10.4 billion The annual cost to Canadians to care for those living with dementia.

Excerpt printed with permission of the author. Choosing Joy: Alzheimer’s: A Book of Hope by Helene Berger. Copyright © 2019. visit www.heleneberger.com.