“If exercise were a pill, it would be one of the most cost-effective drugs ever invented.”

most cost-effective drugs ever invented.”

— Dr Nick Cavill

By Laura Stewart

Everyone needs to exercise: Medical evidence provides overwhelming support for the benefits it provides for every condition under the sun, from arthritis to cancer. The Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Older Adults recommends that those aged 65+ should accumulate 150 minutes of physical activity per week.

But for many people living with disease or injury that affects their mobility, increasing exercise can be an intimidating idea. For those caring for loved ones with pain and disability, messages can be confusing, and it is not always clear who or where to turn for advice.

Who should I be asking about exercise?

A good starting point is your family physician, who will know about any underlying conditions that may limit your activities, or any changes that need to be made to your therapy as a result of a new exercise regimen. But beyond general guidelines, many doctors lack the time and perhaps even the knowledge, to prescribe exercise in a way that is specific, detailed and clear.

Physiotherapists are specialists in the treatment of diseases and conditions affecting mobility, so a great starting place might be to make an appointment for an assessment. Even if you don’t have a specific injury, a physiotherapist can help you identify potential injuries and give you specific exercise advice based on your situation and your particular strengths and weaknesses.

Physiotherapists are specialists in the treatment of diseases and conditions affecting mobility, so a great starting place might be to make an appointment for an assessment. Even if you don’t have a specific injury, a physiotherapist can help you identify potential injuries and give you specific exercise advice based on your situation and your particular strengths and weaknesses.

Personal trainers are another often-used resource. However, they are not regulated health professionals, so you don’t always know how experienced or knowledgeable they are in dealing with specific diseases or injuries. In some cases, the physiotherapist will work with the patient’s personal trainer, Pilates or yoga instructor, or other exercise specialist, to ensure that the exercises are appropriate.

Q) How hard should I exercise and how do I know when to stop?

The short answer is simple: Start very slowly, increase very gradually, and pay attention to cues from your body along the way.

If you have pain during an exercise session, ask yourself if it is simply muscle fatigue or if a specific area is giving you a problem. You may notice your pain actually decreases as you continue with the exercise. This is a green light to continue, although if you are trying a new activity, keep the session short and low-intensity.

If the pain seems to get worse as you exercise, first try modifying the activity (by reducing the intensity, speed, amount of weight lifted or range of movement). If that doesn’t help, stop the exercise for that session. You can try it again another day to see if it still increases your pain.

Whether or not you feel pain during exercise, pay attention to any soreness in your body that night, and for the next day or two. Some muscle soreness is normal—but pain, redness or swelling in your joints are signs you have overdone it. (See “What If It Hurts?”)

Q) What should I try?

Q) What should I try?

Stretching keeps your joints and muscles flexible, and should be a part of any exercise program. One proviso: Many of us grew up being told to stretch before any activity, holding the limb in a position so the muscle group is lengthened for some period of time. In fact, this “static stretching” temporarily weakens a muscle, making it more prone to injury, so it should be done after, not before or during exercise. Hold each stretch for a minimum of 30 seconds, and then repeat each stretch once. Stretching should never be painful.

Strength training is especially important if you have osteoporosis or if your doctor is concerned about your bone density. Those with osteoarthritis can reduce the amount of wear and tear on joints by strengthening the muscles around them. Small dumbbells, and elastic tubing with attached handles, offer good resistance exercise. If sore or stiff hands make gripping difficult, you can purchase cuff weights that attach with Velcro around your wrists and ankles.

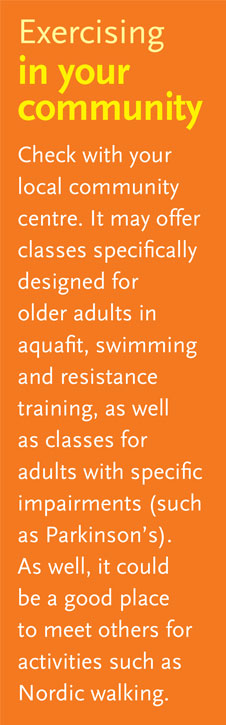

Water exercise may be the right choice if you have any type of arthritis or joint injury. Aquafit classes add some strength training to your cardio workout, while swimming is a wonderful way to get a cardiovascular workout without putting wear and tear on the joints.

If you have shoulder or joint issues, you may find swimming difficult; work with a swimming expert or physiotherapist to modify your technique or to find alternative moves. A note for those with osteoporosis: Although water exercises and swimming are beneficial, they will not improve your bone density, so you should also include some higher-impact walking and/or strength training in your weekly exercise program.

Walking is one of the simplest forms of exercise, and it’s free! This low-impact cardiovascular exercise will be especially helpful for anyone who has high blood pressure or is overweight. A pedometer can help you track how many steps you take each day, and help you chart increased activity.

If you find walking difficult, try using a gait aid such as a cane. A Rollator walker is a walker with four wheels and a seat, and brakes that you can set so the walker won’t move if you sit to have a rest.

Whichever way you decide to walk, make sure you wear supportive  footwear with non-skid soles, and choose a route that is flat and free of obstacles.

footwear with non-skid soles, and choose a route that is flat and free of obstacles.

Balance exercises are important because poor balance and frequent falls are one of the most common complaints of seniors and their caregivers. People with a neurological disease or injury will almost certainly have problems with their balance, as will anyone with reduced sensation in their legs from diabetes, or who has experienced a lower body sprain, broken bone or surgery. But luckily, balance is something that is relatively easy to improve.

It is important to have something to hold on to, and someone else nearby, while you are practising. Start with simple exercises such as balancing on one foot or slowly marching in place with your knees high.

Coordination exercises that challenge your dexterity are especially important for those with neurological impairments. Coordination impairments can result after a stroke, or with neurological disease such as Parkinson’s or multiple sclerosis. Improving dexterity in your hands can be as simple as touching your thumbs to the tips of each finger, one at a time; for more of a challenge, increase the speed at which you tap. For lower extremity coordination, stand at the bottom of a staircase and tap alternate feet on the bottom step. Make sure to keep a firm hold on the railing. Increase the challenge by moving more quickly and relying less on your hands to stabilize you.

Other exercise programs

Exercise options are virtually unlimited in most communities. If you are interested in a class, speak briefly with the instructor beforehand, being honest about any injuries or diseases that may limit your abilities. Ask about class size; a smaller group will mean more one-on-one attention when needed.

Pace yourself and reap the rewards

It cannot be emphasized enough: Start slowly! If your body is not accustomed to doing much, then start on alternate days, to give yourself a day in between to rest and recover. Try introducing one new activity at a time. A resolution to drastically change your exercise habits can be disappointing and frustrating if injury occurs. Keep your family and healthcare team “in the loop” about your exercise plans and results.

Keep a journal of your activities and note any changes in your body that arise. Don’t forget to track the positive changes—improved activity tolerance, faster walking speed, less shortness of breath and

increased energy. Even if the changes are negative, take heart—after all, having a “sports injury” sounds so much better than having the aches and pains of a sedentary lifestyle!

Laura Stewart, BScH, MScPT, is a physiotherapist working in both private homecare and community clinics in Toronto.